1

It was a ghost book. That’s what it’s called in the rare book trade: a book that was advertised somewhere as “forthcoming” or “in press,” and then for some reason never appeared; or maybe an old collector claimed he saw a copy back in the day, or a dealer saw one offered in a catalogue long ago, but neither the book nor the catalogue ever surfaced. Stories. It’s a business built on stories.

But there it was on the glass counter. Robert Ansel was seeing a ghost.

“Where did you come by this?” he asked.

Since the recent death of his business partner, Philip Ames, Ansel was now the sole proprietor of Ames & Ansel Antiquarian Books. He’d seen some wonderful books walk through the door over the years, but never a book like this.

The kid on the other side of the counter shoved his hands into the pockets of his hoodie. The hood was up, but his stringy blond hair spilled out. There was a splatter of pimples on his pale cheeks and nose. He was around eighteen or so, clearly nervous, and showing it with petulance.

“Bought it,” he said. His voice was a challenge. Prove I didn’t.

Ansel smiled and nodded encouragingly. “May I ask where?”

“You interested in buying it or what?”

“Yes, yes, certainly. It’s just something we like to know about the books we represent. Provenance.” Since the kid probably wouldn’t know what that meant, he added, “Where the book came from. Who owned it. The story of the book.”

The kid shifted his weight from one leg to the other. It was clear he didn’t understand, didn’t care. “How much you give me for it?” he asked.

“Well, it’s a somewhat uncommon book. We’d need to do a little research to determine a fair—”

“I ain’t got time.” The kid snapped a hand out of his pocket and grabbed the book. It made Ansel’s heart ache to see this hand with dirty fingernails close upon it. The kid handled it like a library book he was about to shove through the return slot. But no, he didn’t look as if he’d ever set foot in a library.

“Well, without time to research,” Ansel said, “what would you think is a fair price?”

“Three hundred.”

Ansel could hear that it was a rehearsed number, a number the kid had brought in off the street with him. Ansel almost laughed out loud. The book was quite literally priceless. It was possibly—probably—the only copy in existence.

“That’s a lot of money for one book,” he said, and watched the kid’s eyes for signs of uncertainty, of wavering over the price. They didn’t move, but his hand tightened on the book. Ansel feared that at any moment he might pull it off the counter and walk out.

“Okay, I’ll take a chance on it, and research later.” Ansel reached under the counter and pulled out his sales register and check book. “Who can I make this out to?” he asked.

“No check,” the kid said. “I ain’t got a bank.”

Ansel scowled. “May I at least have a name for the sales record? It’s required.”

The kid paused. His eyes moved beyond Ansel, scanning the shelves of books behind the counter.

“Harrison.”

Ansel knew there was a set of Jim Harrison first editions on the shelves behind him.

“First name?”

“John.”

At least it’s not Jim, Ansel thought. He wrote the clearly fictitious name in the sales register, along the with the book’s title and the price paid. This was a crooked sale, and he knew it. But he also knew that if he didn’t go through with it, the book would disappear out the door, possibly never to surface again. It would go back to being a ghost. At least this way he could hold onto it, make inquiries, see if he could find the real owner, uncover its history. And if he wasn’t able to find the real owner, well… He brushed the thought away. It was too thrilling to contemplate.

“Cash, then,” he said, reaching under the counter for his hidden cash box. He kept a small amount of money in the register for change, but there were times like this when a larger cash purchase was necessary. He counted out fifteen twenties below the counter, then again on the glass beside the book. “Three hundred,” he said.

The kid scooped up the bills and, without saying another word, walked quickly to the door and out into the street. Ansel hurried around the end of the counter and caught a glimpse of the hoodie as he passed by the shop window, already beginning to run. By the time Ansel opened the shop door and stepped out onto the sidewalk, the kid was gone.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” he said softly. His heart was beating unnaturally in his chest, and he put a hand on the doorframe to steady himself.

He glanced up at the sky. Dark clouds had been rolling in all day. Rain was forecast, possibly even a thunder storm. Off in the distance the Seattle Space Needle shimmered in a last patch of sunlight. It was nearly five o’clock, still an hour before closing, but he was tempted to flip the sign on the door as he went back inside. He didn’t, though. He thought of Ames, as he often did these days. What would Ames have done?

He’d been seventy-two when he passed away a few weeks before, some thirty years older than Ansel. During their time together, he had taught his junior partner most of what Ansel knew about the rare book trade: how to identify first editions and rare issues, the importance of condition, how to negotiate respectfully as both buyer and seller. Above all, Ames had taught him the almost mystical ethics of what they called “the trade,” the brotherhood of rare book dealers. One rule he’d always insisted on: never buy a book you even suspect of being stolen.

Ansel had just done that.

He went back behind the counter and picked up the book. The navy-blue cloth binding had some rubbing on the tips and at the crown of the spine. The gilt lettering was dull, and there was a bit of foxing on the pages. All that was to be expected, given its age. Nonetheless, the book was in remarkably good condition. He opened the cover carefully and examined the title and copyright pages. “The Brothers Karamasoff, A Russian Realistic Novel by Fedor Dostoieffsky, Vizetelly & Co., London, 1888. Authorized translation by Anton Moresby.”

Henry Vizetelly had first issued a translation of Crime and Punishment in 1886. In the ads at the back of other titles, well into 1887, he’d advertised five other Dostoevsky volumes as available or forthcoming, all of which did indeed appear, except Karamasoff. Twenty-five years later, in 1912, the Constance Garnett translation of The Brothers Karamazov appeared, the first of her translations of Dostoevsky’s complete works. Her introduction hinted obliquely at a previous version, but none had ever been found—not in the antiquarian book world, nor in the WorldCat online database of holdings in the world’s largest libraries. It remained one of the great mysteries of the rare book trade, and Ansel, like almost all book dealers and Dostoevsky collectors, had assumed it didn’t exist. Yet here it was in his hands.

He heard the shop door open and glanced up. It was one of his regular customers, or rather browsers, for the man rarely bought anything. A gaunt old man, with sunken cheeks and dark, hollow eyes. Whenever he reached out to pull a book from the shelf, he hesitated, as if fearing he might receive a static shock when his fingers touched the binding. For some reason he reminded Ansel of a stick bug he’d seen on a nature program on TV, surreally thin, camouflaged against a background of twigs and dead leaves. Ansel found himself wondering if one day he would be like this old man, a brittle, desiccated old specimen, pulling brittle, desiccated volumes off brittle, desiccated shelves. Or possibly still putting them on the shelves.

Ansel slipped the Karamasoff under the counter, out of sight. “Afternoon,” he said.

“Afternoon,” the man whispered, and made his way over to the Northwest History section, his usual haunt.

While the man scanned the shelves, Ansel opened his laptop and began a web search for Anton Moresby, the translator of the Karamasoff. Ansel had seen a lot of Russian lit come into the store over the years and knew the translators fairly well. Constance Garnett, of course, had brought out most of the Russian greats in the early twentieth century, producing readable but not necessarily faithful translations. The earlier translators, from the 1880s, during the “Russian craze” that first brought Tolstoy, Gogol, Dostoevsky and others to public notice in the English-speaking world, were a more shadowy group. Ansel knew that the first editions in English of Crime and Punishment and War and Peace had actually been translated from French editions, not directly from the Russian. But he’d never heard of Anton Moresby, and his internet search turned up nothing.

When the stick bug left, Ansel pulled out his cell phone and dialed Mysterious Island Books, the only other antiquarian bookshop left in the Pioneer Square district. Mysterious Island specialized in sci-fi/fantasy and mysteries, but there was a fair amount of spillover between the two stores’ clientele, and Ansel was friendly with Michael Wells, the owner.

“Hey, Mike. It’s Rob.”

“How’s traffic?” said Wells.

“Pretty light. Hey, have you had anything interesting walk in the door today? Anything special?”

“Box of book clubs I didn’t take. Nothing else.”

“How about a young guy, a teenager, wearing a hoodie? Did he come by your shop?”

“No…” Wells drew out the word, clearly interesting in where this was leading. “Something get lifted?”

“Are you closing at six? Why don’t you stop by?”

“Can’t it wait? I’ve got great seats for the Mariners game, and it’s—”

Ansel cut him off. “Miss the first inning,” he said. “You’re not going to believe what’s sitting here on my counter.”

Wells was the only person he could talk to about the Karamasoff. Once there had been a half dozen or so shops in the area—some small, to be sure, but a few with inventories much larger than either of theirs. That had been the golden age of the trade, Ansel realized now, and he thought back to those years with a kind of aching nostalgia. It had been an old boys’ club back then. Everyone knew each other, knew each other’s stock and specialties, referred their customers to each other. They weren’t really in competition; they were more like gold miners with claims on the same river, sluicing the same bottom soil; whenever one of them turned up a rare and valuable nugget, everyone celebrated.

The internet had changed all that. First eBay, then a handful of sites dedicated to antiquarian books, and finally the big online retail booksellers all chipped away at the business. Fewer and fewer customers walked in the door, and more alarming still, fewer sellers brought in their boxes of old books to be picked over for rare finds. One by one, Ansel had seen the other bookshops in the area close, until only his and Wells’s shop remained. Since the death of his partner, Ansel himself had been wondering if it wasn’t time, finally, to shut things down.

Wells arrived a little after six. Ansel had already flipped his sign to Closed, but he’d left the door unlocked. When Wells entered, a gust of cold wind slipped in with him.

They hadn’t seen each other since Ames’s funeral. Ansel had sat up front with Ames’s wife, Alice, and his adult daughter from a previous marriage, while Wells had settled into a back pew with a few older book dealers who’d known Ames. They’d all worn the same “which one of us is next” expression on their faces. So many dealers had retired and more or less disappeared from the trade that it was a hard blow to lose Ames, who, as one of them suggested, had fallen in the line of duty.

“Here as summoned,” Wells said. He was wearing a Mariners jersey and cap, the brim of which was askew, giving him a vaguely comical look.

“Hey, Mike,” Ansel said.

“This better be good. I’ve got a feeling the Mariners are going to stage a miraculous comeback.”

Ansel gave him a look. “Which Mariners are we talking about? It’s mid-September, and they’re what, twelve games back?”

“If they have a big night, we could cut that down to six easy.” Wells said, and paused for a hearty laugh. He was a big man, and his laughter filled the shop. He went to several games a week when the Mariners were in town, and Ansel suspected he ate a great many of his meals at the ballpark and the sports bars that clustered around it. It showed, mostly around the middle. Ansel could see the jersey’s buttons straining at his gut, little pink wedges of flesh with the occasional wild belly hair showing in the gaps between.

“So, what’s up?” Wells asked, propping his elbows on the steel frame of the counter.

Ansel pulled the book out and laid it on the glass, then waited. If there had been an old mechanical clock on the wall, he thought, this was where they’d hear it ticking.

Wells gazed at the book, a puzzled expression slowly forming on his features, then looked back up at Ansel.

“What?” he said.

“It doesn’t exist,” Ansel explained.

Wells leaned over the counter and looked at it from up close. Then he squatted down and squinted at it from various angles. “Seems real to me,” he said finally. “What am I missing?”

Ansel told him about all he’d researched that afternoon and what he’d come up with, which was exactly nothing. “Except for the Vizetelly ads, there is no reference to it anywhere. I know Russian lit isn’t your field, but everyone has always assumed this is a ghost book, that it was never published. And yet, there it is.”

Wells picked up the book, gently now that he understood its rarity. He looked at the title and copyright pages, then at the ads in the back. “Where did you pick it up?”

“The kid with the hoodie. The one I mentioned when I called you. He walked in, with just the one book. He asked three hundred for it, firm. Wanted cash, and then ran out.”

Wells gave Ansel a long, inquiring look. “Stolen book?” he said finally.

“That’s my guess,” Ansel answered. “But I figured, if I didn’t buy it, it would disappear. The kid was nervous. I thought he was going to run off any minute. At least now…” He let the words trail off. At least now what? Weren’t those the first words of some easy justification?

Wells was on the verge of saying something. He hesitated, his mouth slightly open.

“I know, I know,” Ansel said.

Wells sighed. “Well, what’s done is done. What are you going to do with it now?”

“Ask around. Research. See if I can find the real owner, get it back to them. Right now, I’d just like to know where it came from and why there aren’t any references to an actual copy of it, anywhere.”

“It may have been a trial binding,” Wells suggested, turning the book over in his hands. “Or maybe an advance copy sent out for review or copyright, and then…maybe the printers’ shop burned down. Plates and all the copies destroyed.”

“That’s what I was thinking,” Ansel said. “Or it got suppressed for some reason. But I’ve read The Brothers K., a couple times actually, and there’s nothing sexy or subversive enough that anyone would want to suppress it.” He shrugged. “I’m going to keep it under the counter while I look into it. If it was stolen, it might show up in the ABAA database of stolen books, or maybe word will get out in the trade blogs.”

Outside, a white delivery truck, caked with mud on its undercarriage and siding, paused in front of the shop. They both turned to look at it. It rumbled there for a moment, making the plate-glass shop window vibrate, then gave out a rattling grind of gears and moved on in a cloud of diesel exhaust.

“Anything new on the Ames widow situation?” Wells asked, as silence eased back into the shop.

Ames’s wife—now widow—was furious that he had left his half of the shop to Ansel. It was an aggravating stress for Ansel on top of the sorrow of losing his partner, and one he still hadn’t figured out how to navigate.

“I saw her last Friday in the lawyer’s office,” he said. “She insisted on an ‘official reading of the will,’ although it was only the lawyer and Alice and me, since Ames’s daughter had already gone back east. Alice showed up in full grieving-widow regalia—black lace gloves, veil, the works.”

“You’re kidding me.”

“Wish I were.”

It had been a painful hour that had left Ansel shaken and saddened, and also a bit angry. He’d done his best to get along with Alice, but there was something off about her, something scheming and possessive, it seemed to him. The few times he’d joined them for a meal or she’d dropped by the shop for some reason, it had been a strain. It was almost as if Alice saw Ansel as a romantic rival, as if he and Ames had been more than just business partners and close friends.

Ames had married Alice some five years before, quite suddenly. Ansel hadn’t even met her yet, but had been vaguely aware that there was something going on in Ames’s life outside the shop. He’d left early some days, telling Ansel to lock up, and a couple times he’d gone off for long weekends with no explanation. Ansel had actually asked him about it one day, but received just a sly smile in response. And then, one day, Ames had asked him to come down to the courthouse and be a witness for his wedding.

There he’d met Alice. She’d looked a good twenty years younger than Ames—in her late forties, Ansel judged, although it was hard to be sure. Her hair was dyed auburn, and her makeup was fastidiously applied, so there might have been some deception involved. On the other hand, it was her wedding day, so why wouldn’t she try to look her best? And she’d been pleasant and friendly, standing there in her summery dress, a sprig of lavender pinned to one lace lapel, and a pair of modest shoes, scuffed at the toes. The county clerk, visibly bored, had read the ceremony, and the couple had exchanged simple rings and a glancing kiss under the harsh florescent lights. Ten minutes, and it was done.

It hadn’t been long before cracks began appearing in the marriage, and soon Ames was the one staying late at the shop. He’d been a gregarious man, especially when discussing books, but about his private life he’d remained surprisingly reticent. Only occasionally did he let slip some remark indicating his regrets. Still the marriage had somehow endured up until the end, until the day when he fell to the bookshop floor and never got up.

“The lawyer,” Ansel said to Wells, “told Alice that this official ‘reading of the will’ thing only happened in the movies. He’d never actually read a will out loud to anyone. The beneficiaries simply got copies, and then they got together to iron out any details. But she was adamant. ‘Read it! Read it!’ she said. Or barked, I guess, would be a better description. She was fuming, beside herself.”

“She didn’t know what was in it already?” Wells asked.

“Well, she’d received a copy, so she must have. But she wanted to hear it again. So the lawyer reads it out loud, and it’s pretty short. His half of the shop goes to me, his house to his daughter. Alice was given his liquid financial assets, which can’t have been all that much, plus his car and furniture and that kind of thing.”

“Jesus,” Wells said, shaking his head. “That must have hurt. His own wife.”

“I’m sure it did. When the lawyer finished, she leaned forward, slapped the desk, and shrieked, ‘I contest this will! I contest it! I contest it!’ She was practically unhinged. I was afraid she was going to pull out a gun and shoot us both.”

“And now she wants the shop? Is that it?”

Ansel shrugged, then said wearily, “Some days I’m tempted to give it to her. Ever since Ames died…”

They both looked down at the floor, the floor where Ames had fallen from a massive heart attack. In the silence that grew between them, they could hear the first roar of the stadium crowd.

“And then a book like this appears,” Ansel continued, gesturing at the Karamasoff.

“Keeps us opening our doors, right?”

Ansel nodded.

“Well, I’d better go get myself some beer and hot dogs,” Wells said, slapping his gut with a laugh. He turned and headed for the door. “Kid with a hoodie, huh?” he added over his shoulder. “If I see him out there, I’ll pin him up against a wall and shake the story out of him.” He gave another laugh, then opened the door and walked out into the street.

Ansel came around the counter and locked the shop door after him, then stood for a moment, gazing out at the darkening streets. As if, he thought, chuckling at the image—as if stories were just so many pennies to be shaken from the pockets of thieves.

—

Author’s Statement

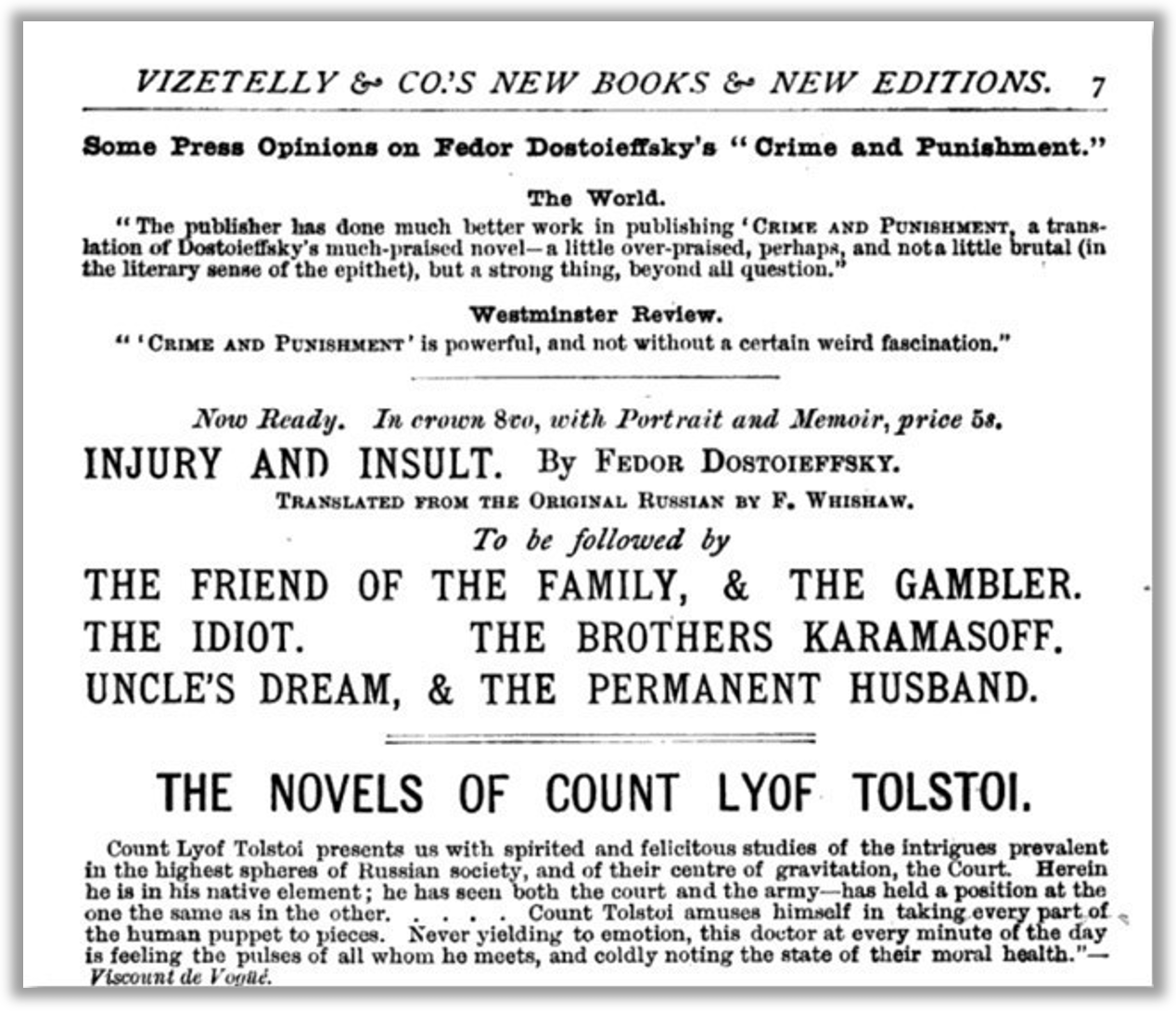

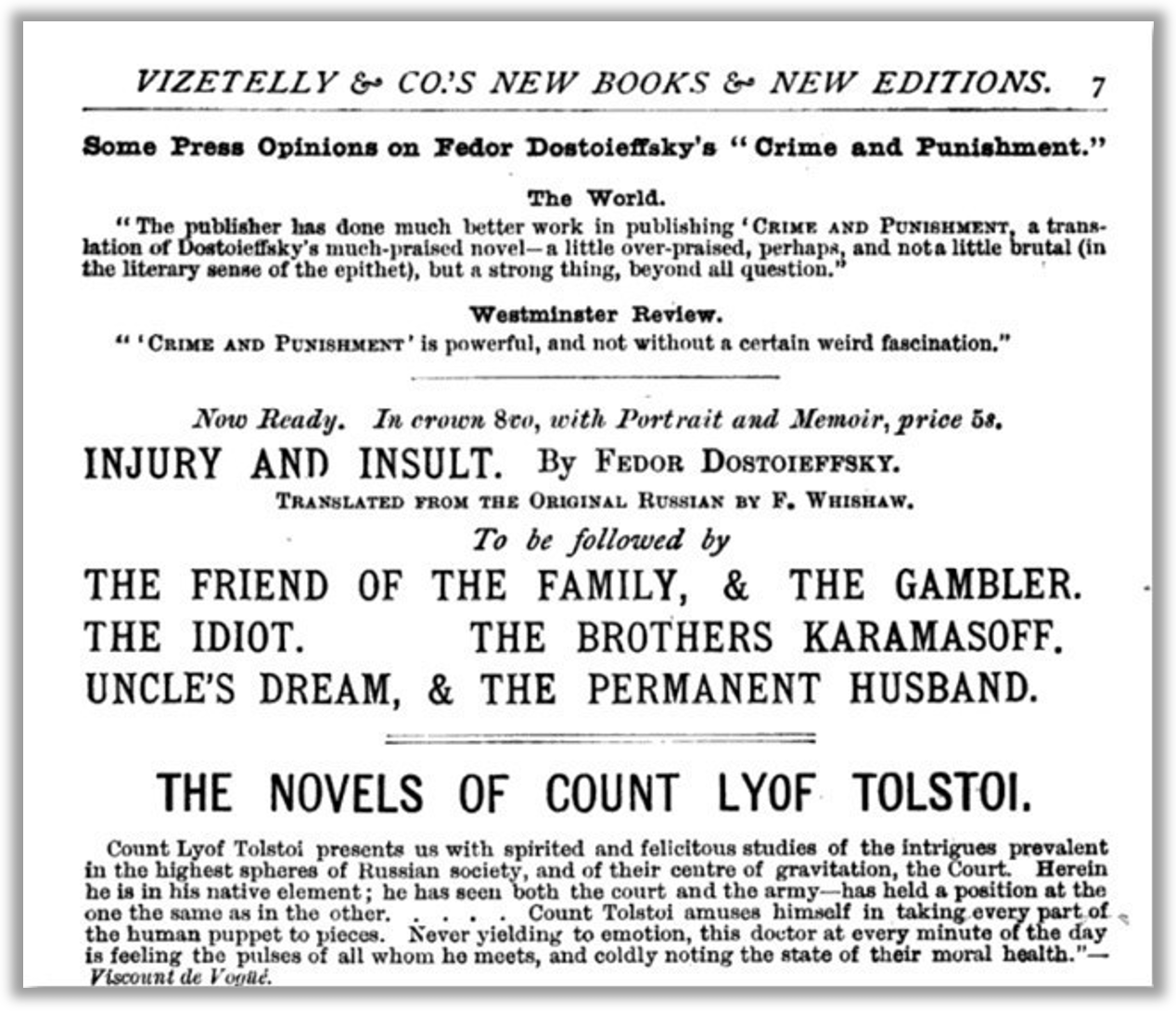

THE GHOST KARAMAZOV is, in a sense, a mystery without a murder. Its inspiration comes from an obscure advertisement in an old book. In the 1880s, the London publisher Henry Vizetelly brought out the first English translations of some major Dostoevsky novels, including Crime and Punishment and The Idiot.  He also advertised The Brothers Karamasoff as forthcoming (see the image to the right of an ad from 1887), but the book never appeared. It became what is called in the rare book trade a “ghost book.” The premise of my novel is that the book was actually published and then suppressed, with only a single copy escaping into the world.

He also advertised The Brothers Karamasoff as forthcoming (see the image to the right of an ad from 1887), but the book never appeared. It became what is called in the rare book trade a “ghost book.” The premise of my novel is that the book was actually published and then suppressed, with only a single copy escaping into the world.

He also advertised The Brothers Karamasoff as forthcoming (see the image to the right of an ad from 1887), but the book never appeared. It became what is called in the rare book trade a “ghost book.” The premise of my novel is that the book was actually published and then suppressed, with only a single copy escaping into the world.

He also advertised The Brothers Karamasoff as forthcoming (see the image to the right of an ad from 1887), but the book never appeared. It became what is called in the rare book trade a “ghost book.” The premise of my novel is that the book was actually published and then suppressed, with only a single copy escaping into the world.THE GHOST KARAMAZOV is structured like a classical triptych, with the smaller end panels set in the present day and the larger central canvas spanning more than a century and containing a multitude of characters. In Part One, Robert Ansel, a rare book dealer in Seattle, acquires a copy of this ghost book and works to uncover its origin, while wrestling with his own personal demons. Part Two follows the book as it changes hands over the years, exploring the interwoven stories of the people who owned it, beginning with the translator in Victorian England and ending with Ansel in present-day Seattle. Part Three of the novel continues his story, as he makes a journey to St. Petersburg, Russia, to learn the book’s mysterious history.

One of the most challenging aspects of writing THE GHOST KARAMAZOV was to give a sense of Dostoevsky’s great novel without any expectation of my readers having read the book. I also resisted the impulse to align the themes of Dostoevsky’s work with the lives of my characters, believing it would come off as too schematic. Rather, I’ve used The Brothers Karamazov, both as a masterpiece of world literature and as a talismanic object of the rare book trade, as a leitmotif in my novel. In the end, THE GHOST KARAMAZOV is not really about a book at all, but about the lives of the people who have been touched by it.

David Norling has published a number of stories in literary journals, and is currently at work on another novel. He lives in the Pacific Northwest.

Embark, Issue 21, October 2024